October 2024 LSOG Report

Click on the image above to download the report (PDF).

PROJECT GOAL: To map late-successional and old-growth (LSOG) forest in the unorganized territories of Maine so timberland owners and conservation groups can work to conserve this increasingly uncommon forest age-class.

The 10-million acres of unorganized townships of Maine are unique in the eastern U.S. The area is nearly 100% forested and lacks the agricultural or ex-urban development of most of the eastern U.S. At night, the area is an enormous dark “hole” on the U.S. map. Although mostly managed for timber production, the area is a haven for wildlife species, from migratory birds to lynx and moose. Its rivers still provide habitat for many aquatic species, such as cold-water brook trout and the endangered Atlantic salmon. In short, the unorganized townships of Maine are a rare gem of global ecological significance.

However, because about 85% of these 10-million acres are privately owned and managed by timber companies, it can be financially difficult to retain late-successional and and old-growth (LSOG) forest in the mix of forest types and age classes. Stands older than 60 or 80 years of age are usually past their financial prime. Yet late-successional forest (100-200 years old) and old-growth forest (>200 years old) develop ecological characteristics such as large living trees, large dead trees (snags), and large logs on the forest floor. All of these structural attributes of old forest are important to a wide range of species, from nesting raptors such as the Goshawk, to less charismatic but highly sensitive mosses and lichens. The undisturbed temporal continuity of these older stands can also be important for species that do not disperse very fast through the landscape.

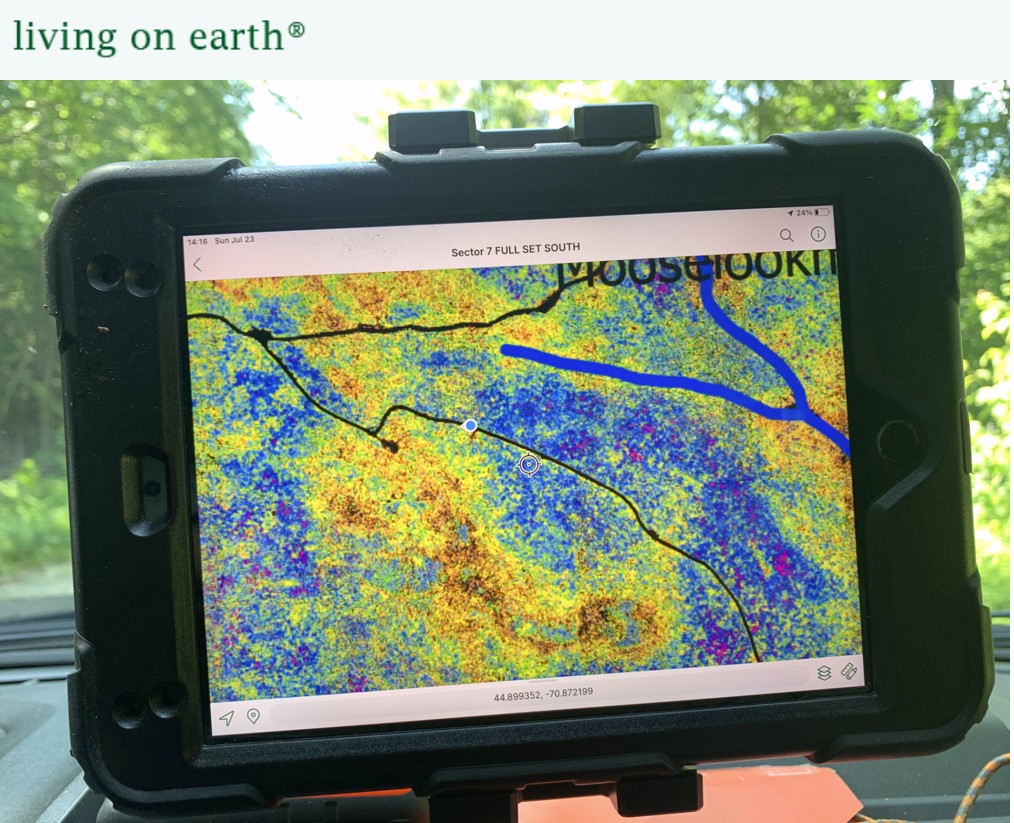

One big challenge to conserving LSOG forest over such an enormous area as the unorganized townships of Maine is knowing how much there is, and where it is. In this study, we explored the ability of LiDAR (light detection and ranging) to map and quantify LSOG forest. We used publicly available LiDAR data flown between 2015 and 2018 to map LSOG forest in Maine. This first project focused on the hardwood, softwood, and mixedwood forests that are most at risk to timber harvesting (loss). Future work will focus on mapping forested LSOG wetlands, such as cedar swamps.

As you will see in our report, we have a new tool that can help society think through how much LSOG forest we want and how we want it distributed. Land managers and conservation groups will both have a role to play. Our new maps will help. Our report outlines a number of strategies different stakeholders might use to conserve this important and diminishing age class of forest. We stand ready to help anyone who has an interest in conserving old forest in Maine.

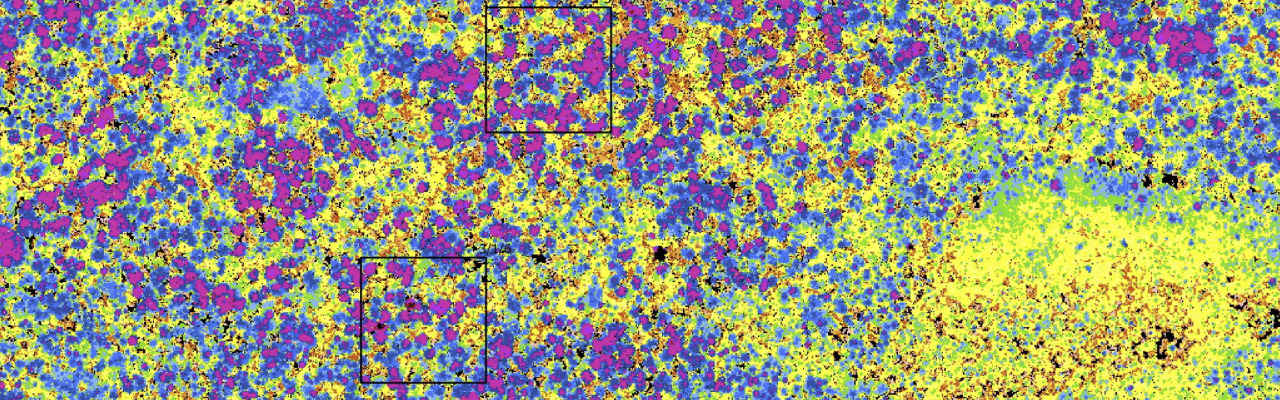

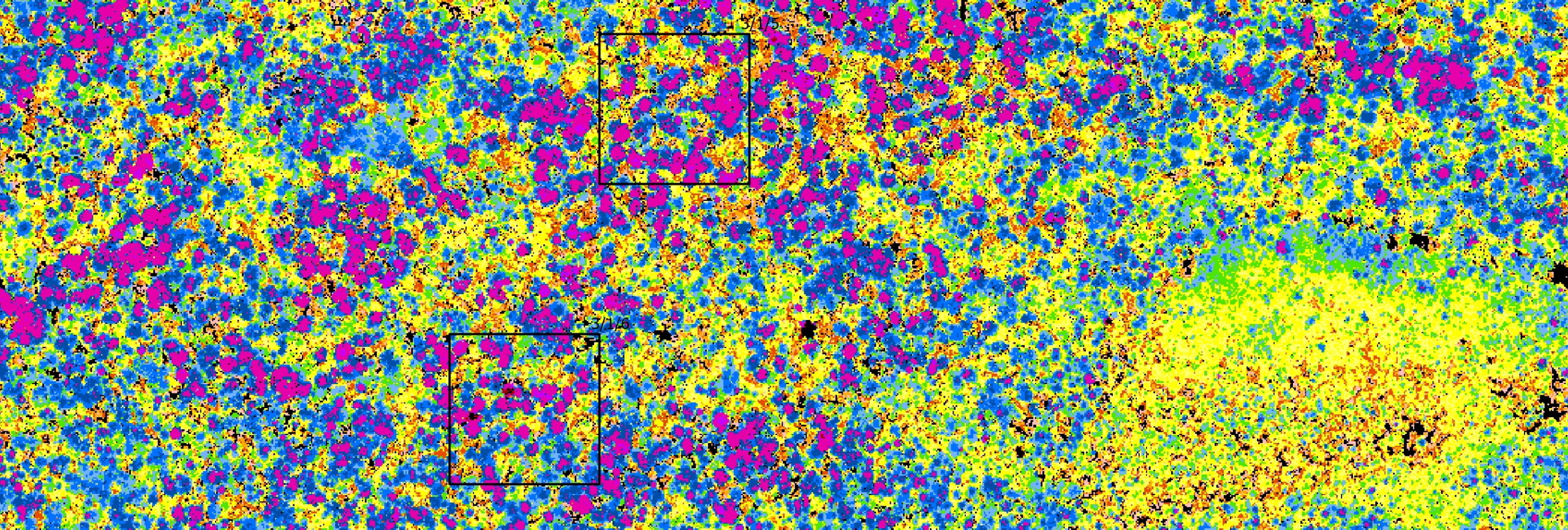

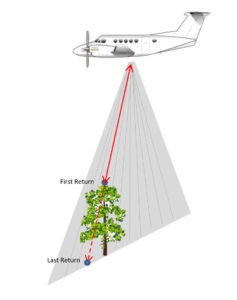

How LiDAR Works

LiDAR stands for Light Detection and Ranging. It involves firing a laser beam, usually from an airplane, toward the ground (see below). The laser beam is reflected off of anything it hits, both the trees and the ground below. Because the laser beam is moving at the speed of light, the difference in the time it takes the first return to get back to the plane and the last return to get back to the plane tells us how tall the tree is. That is, the time difference is converted to a very accurate tree height (within 10 cm). Some of the laser beams bounce off of tree branches. The end result is a massive digital “point cloud” that creates a 3-dimensional view of the forest. The usable resolution of the publicly available LiDAR is a 1 square meter– extremely fine resolution compared to satellite imagery (30×30 m, or 10x10m).

PROJECT TEAM

John Hagan, Ph.D., Our Climate Common

Ben Shamgochian, Our Climate Common

Molly Taylor, Tufts University

Michael Reed, Ph.D., Tufts University

PROJECT FUNDERS

Cooperative Forest Research Unit, University of Maine

Daniel Hildreth

Maine Timberlands Charitable Trust

The Arboretum Fund of the Maine Community Foundation

The Betterment Fund

The Dorr Foundation

The Emily J. Knobloch Foundation

The Horizon Foundation

LANDOWNER PARTNERS

Appalachian Mountain Club

Baskahegan Co.

Baxter State Park

Huber Resources Corp.

Irving Woodlands

Landvest

Seven Islands Land Company

The Nature Conservancy

The Weyerhaeuser Co.

Wheatland Geospatial Lab

LSOG Working Group

Kyle Burdick, Baskahegan Co.

Shawn Fraver, University of Maine

Jake Metzler, Forest Society of Maine

Neil Pederson, Harvard Forest

Shelby Perry, Northeast Wildnerness Trust

Justin Schlawin, Maine Inland Fisheries and Wildlife

Andy Whitman, Maine Forest Service

LSOG Rapid Assessment Protocol (RAP) 2025

Click on the image above to download the report (PDF).

PROJECT GOAL: To quickly, efficiently, and accurately determine whether a forest stand is Transitioning late-successional, late-successional, or “Not LSOG.”

In 2024, we mapped LSOG forest in the unorganized townships of Maine using publicly available LiDAR (light detection and ranging) data (Hagan et al. 2024). The computer algorithm we used to build the map depended on having known reference sites– ground-verified LSOG stands the computer could use to “learn” what an LSOG stand looks like in LiDAR.

At the conclusion of the LSOG mapping project we realized that others might find our field classification method useful in their own forest management or land conservation activities. Though our maps proved to be correct over 90% of the time, there were still exceptions—false negatives (the map said the stand wasn’t LSOG, but it really was) and false positives (our map said the stand was LSOG, but it really wasn’t on the ground). In our October 2024 report, we encouraged land managers to screen any LSOG stands indicated on our map before making management decisions. “Trust but verify.”

In this report (the LSOG RAP) we describe a new field method for identifying late-successional and old-growth (LSOG) forest in Maine’s unorganized townships. Once on site, the method only takes 15-20 minutes. The data can then be entered into an online app that instantly calculates the probability the stand is (1) Not LSOG, (2) Transitioning LS, or (3) LS forest (see Table 1 in the RAP report). We hope forest managers, field biologists, and others will find the LSOG Rapid Assessment Protocol to be easy to use and helpful in making practical, stand-level management decisions for LSOG stands.

LSOG Project in the news…

Click on the image below to play story

Click on the image below to play story